Google this week updated Chrome to version 76, patching 43 security flaws and making good on a promise to switch off Flash by default.

The company paid out $28,000 — more than three times the last cycle — in bug bounties to a half dozen researchers who reported a few of those vulnerabilities. Five of the flaws were ranked “High,” the second-most-serious category in Google’s four-step ratings, including one that paid $10,000 to its discoverer and another that garnered $6,000. None were rated “Critical,” the topmost threat.

Because Chrome updates in the background, most users only need to relaunch the browser to finish the upgrade. To manually update, select “About Google Chrome” from the Help menu under the vertical ellipsis at the upper right; the resulting tab shows that the browser has been updated or displays the download process before presenting a “Relaunch” button. New to Chrome? Download the latest in versions for Windows, macOS and Linux.

Google updates Chrome every six to eight weeks. It last upgraded the browser on June 4.

Last anti-Flash step before Chrome nixes it altogether

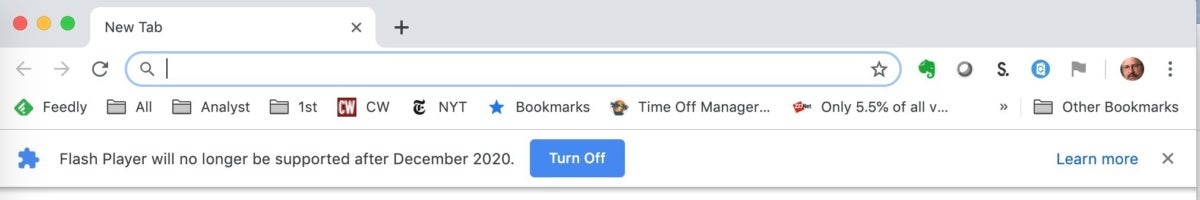

With the debut of version 76, the browser disabled Flash by default, the state Chrome will remain in until all support is yanked in late 2020.

Sites requiring the plug-in will show the “missing puzzle piece” symbol and the message “Adobe Flash Player is blocked.” Users will not be able to run Flash — at all — without going into Settings. After re-enabling Flash at Settings > Advanced > Privacy and security > Site Settings > Flash > Ask First (that last is done by toggling the switch from Block sites from running Flash (recommended)), Chrome users can again run Flash and display Flash content but only after authorization through a click.

Note: IT-set group policies that manage Flash within Chrome were not affected by the version 76 change. You can still control Flash behavior using DefaultPluginsSetting, PluginsAllowedForUrls, and PluginsBlockedForUrls, Google said.

Chrome now leads the second-place browser, Mozilla’s Firefox, in deflecting Flash. (The only browser further along, Apple’s Safari, has been anti-Flash since 2010, when Cupertino told users to fetch Flash themselves.)

And Google came through with the “infobar” it had pledged previously. If the user manually switches Flash back on through Settings, the infobar appears, warning that the plug-in won’t be supported at all after December 2020. It also offers a link for more info on the ban.

Currently, Chrome is to completely nix support for Flash as of version 87, which should debut in December 2020.

Chrome slams door on Incognito Mode loophole

Chrome 76 also closed a loophole that some websites were exploiting to shut down users trying to slip past article count meters.

Many sites with paywalls — the New York Times, for one — let visitors view x number of stories free of charge, a way to show the quality of the content behind the wall. After that count is reached, access is blocked. Browsers’ privacy modes, including Chrome’s Incognito Mode, were a way for readers to “reset” that meter and read more than the allotted number of articles.

Site publishers, of course, were onto the privacy mode ploy and in Chrome, monitored an API that was automatically disabled in Incognito Mode. If a call to the API returned an error — as it did when the API was off — the site assumed the visitor was in privacy mode and then blocked them from reading.

Two weeks ago, Google announced it was shutting down the ability of sites to sniff out Incognito Mode through the API. “Chrome will likewise work to remedy any other current or future means of Incognito Mode detection,” promised Barb Palser, a manager in Google’s news and web partnerships group, in a post to a company blog.

She also had recommendations for site publishers who had used the API to detect story count scofflaws. “Sites that wish to deter meter circumvention have options such as reducing the number of free articles someone can view before logging in, requiring free registration to view any content or hardening their paywalls,” Palser wrote. “Other sites offer more generous meters as a way to develop affinity among potential subscribers, recognizing some people will always look for workarounds.”

Site publishers could be excused for breezing by Palser’s unsolicited advice, seeing as how Google’s business model is the antithesis of most sites’.

PWA isn’t the sound you make when you spit

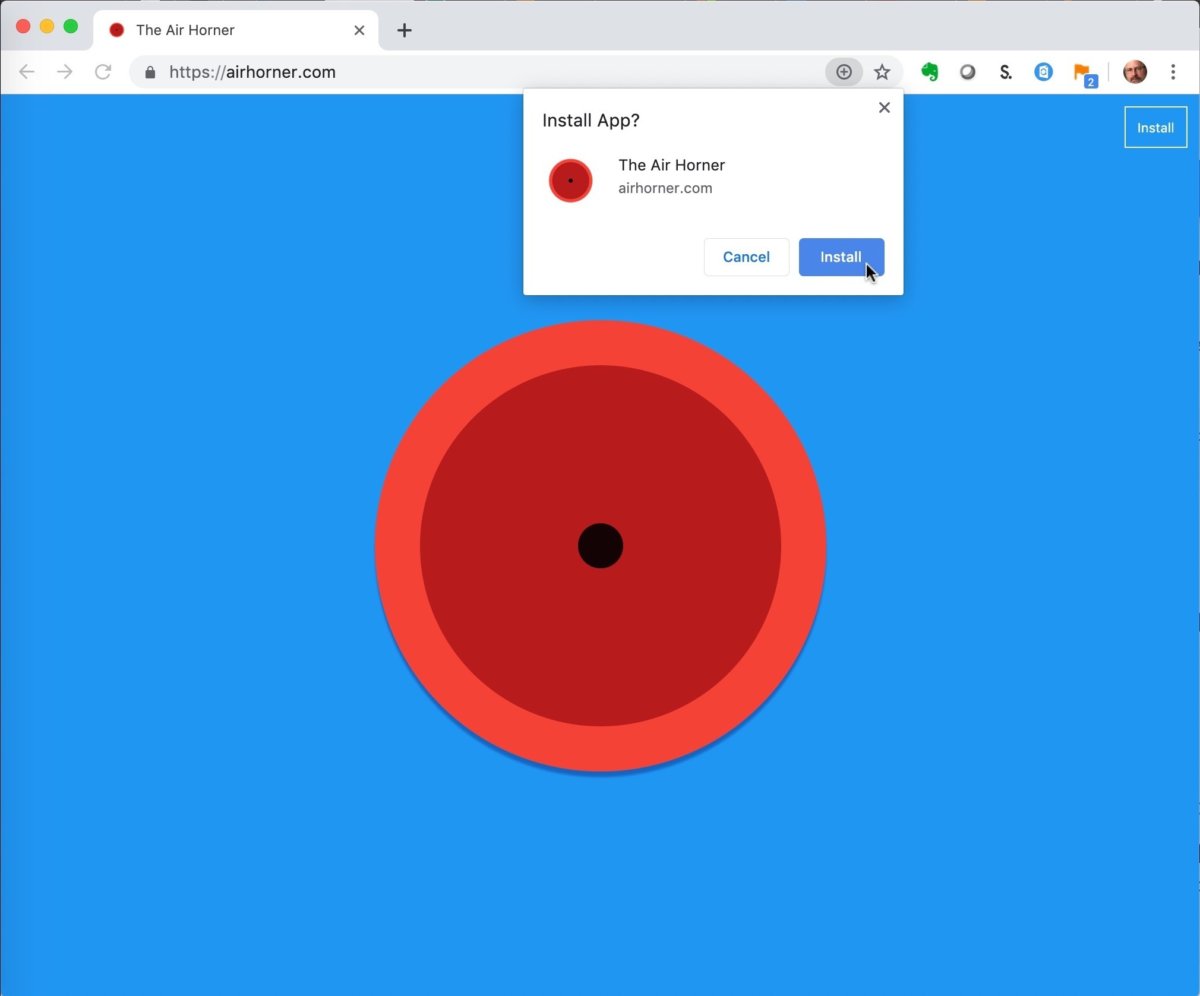

As another part of its push to boost Progressive Web Apps (PWAs), the platform-independent apps that behave much like standard desktop applications, Chrome 76 simplifies their installation.

If the distributing website meets the PWA install criteria, Chrome now displays a small icon at the right edge of the address bar; clicking that icon initiates the PWA installation process. By bringing PWA availability to the forefront, Google hopes to raise awareness of the standard.

“On desktop, there’s typically no indication to a user that a Progressive Web App is installable, and if it is, the install flow is hidden within the three-dot menu,” wrote Pete LePage, a Google developer advocate, in a June document. “We’re making it easier for users to install Progressive Web Apps on the desktop by adding an install button to the address bar.”

(Not surprisingly, Chrome is a huge booster of PWA; Google coined the term.)

For enterprise eyes only

A few of Chrome 76’s additions and improvements are only for organizations that manage the browser.

As of this version, private-hosted Chrome add-ons — in other words, those not in the Chrome Web Store e-market — must be packaged with the CRX3 format. (The prior format, CRX2, used the SHA1 cryptographic hash function to secure extension updates; CRX2’s SHA1, however, can technically be broken, potentially giving attackers who intercept an over-the-Internet update a way to inject malicious code into the add-on refresh.)

“If your organization is force-installing privately hosted extensions or third-party extensions hosted outside of the Chrome Web Store that are packaged in CRX2 format, the extensions will stop updating in Chrome 76 and new installations of the extension will fail,” Google warned.

Chrome 76 also nulls the ability of IT staffs to use group policies to opt out of the site isolation technology Google introduced in 2007 with version 63. A year ago, Google switched on site isolation for the vast majority of Chrome users.

But because site isolation impacted Chrome’s performance, Google has let enterprises that manage the browser disable the defensive technology. That’s now ended.

“Starting with Chrome 76, we will remove the ability to opt out of site isolation on desktop using the SitePerProcess or IsolateOrigins policies,” Google announced. The change only applied to desktop Chrome, including Chrome OS; on Android, the comparable SitePerProcessAndroid and IsolateOriginsAndroid policies can continue to be used to turn off site isolation.

Google has also created a new Chrome policy list for enterprise IT. Notably, the list can be filtered by platform — macOS, Windows, Android and the like — as well as by Chrome version.

Chrome’s next upgrade, version 77, should reach users on or about Sept. 10.